Scott Adams has been blogging recently about Cheapatopia.

Cheapatopia is a hypothetical city, designed from scratch to be an absurdly cheap place to live with a ridiculously high quality of life.

It got me thinking about an idea some friends of mine and I had back in my younger days. We called it the Promune, for Professional Commune.

I have been exposed to two examples of intentional communities in my life. Back in 1984 I spent a week at Twin Oaks, which is near Louisa, Virginia.

From their website:

We do not have a group religion; our beliefs are diverse. We do not have a central leader; we govern ourselves by a form of democracy with responsibility shared among various managers, planners, and committees. We are self-supporting economically, and partly self-sufficient. We are income-sharing. Each member works 42 hours a week in the community’s business and domestic areas. Each member receives housing, food, healthcare, and personal spending money from the community.

It was a really amazing week. You might be thinking to yourself “Hey, 42 hours a week is more than the 40 I work” but this includes meal preparation, laundry, yard work – pretty much a lot of what you would do outside of your actual job. What amazed me is that these 100 people live near the poverty level as calculated by the government, yet their standard of living is much, much higher. Meals are prepared and served for you, your laundry is done for you – some of the things we associate with the rich.

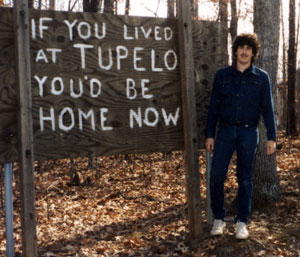

Me at Twin Oaks, circa 1984

Flash forward 15 years and I am buying a farm in Chatham County, North Carolina. Right next to me is another intentional community called Blue Heron Farm.

Blue Heron is more individualistic than Twin Oaks in the sense that there really isn’t as much shared housing and living (folks at Twin Oaks live in a dormitory style arrangement and share meal preparation, etc.) The folks at Blue Heron tend to have their own houses, but they also have a lot of community oriented activities such as a community garden, project weekends and “pot luck” meals. I was there this weekend dropping off a load of horse manure and I couldn’t help but notice how pleasant it was on their land. Again, here is a group of people living together with a much higher standard of living than they could accomplish individually.

Note: At least one person who reads this blog also knows Blue Heron, and there is a chance that someone from Twin Oaks may see this as well, so let me stress than I am oversimplifying the experience at both these places, and in the case of Twin Oaks, my time there was nearly 25 years ago.

So, back to the Promune. Think about things that we usually associate with wealth in this country: land, big house, nice cars, etc. In almost all cases most of the “luxury” items are rarely used. Unless you have a big family my guess is that most of your house is often empty. In my own modest farm house someone is upstairs less than 30 minutes a day on average, unless we have guests.

But it is still nice to have that space when we do have guests, just like it would be nice to have a billiard room, a library, a gym, a music room, a home theatre, a gourmet kitchen, a swimming pool, a Ferrari and a ski boat.

While my experiences with intentional communities revolve around people who are into sustainability (“live simply so others might live”), the idea of the Promune was to see what would happen when you throw, for lack of a better phrase, conspicuous consumption into the mix. If people near the poverty level can live like the middle class, what would happen if you started with the middle class?

Like Blue Heron, the Promune would be organized as a corporation in which people would buy shares. The initial investment would go to buy land, since we’d want on the order of 50-100 acres just to have the room. Central to the community would be the “manor house” which would be similar to what a single wealthy individual might build. While it would contain the billiard room, library, home theatre, guest quarters, etc. no one would actually live in the manor house. Instead, everyone would get individual small bungalows around the property. These would contain a kitchen, living area and bedrooms. You wouldn’t need specialized rooms since those would be in the manor house.

Being geeks at heart, the Promune would be technologically advanced. There would be a fat pipe to the internet, which would be shared around the property. So-called “green” building techniques would be used, and each house would have an electric cart to easily get from their bungalow to the manor house (recharged via solar cells – natch).

Many of my friends have jobs where they work from home, so it would be possible to have a business center in the manor house where people could work together. Depending on how much money was available, there could also be a staff to help keep the common areas clean and perhaps even a cook to plan and prepare meals.

Of course there would be the stable of toys such as sportscars, motorcycles and a boat or two. The swimming pool and tennis courts could be added near the manor house as well.

Sounds good, huh?

I’m not sure why we never gave this a go. Part of it is that we all went our separate ways. Another part is that society isn’t really structured for shared property. Most home owners in the US have a good portion of their assets in their house (along with value appreciation), so how would equity be split? It would be easy to do on a per share basis, but the shares wouldn’t be very liquid.

So speaking of splits, how would one handle a divorce within the community? Would there be limits on children? Twin Oaks realized early on that it had to have a certain ratio of children to adults in order to function (I had been told that communities such as The Farm in Tennessee were nearly 50% children) but would that be required or even work on the Promune (our original vision of the community was primarily for DINKs)?

The Promune would have the best chance of working with a small group of people, unlike the “city” that Adam’s envisions in Cheapatopia, but would it be possible to find enough people to make it viable? I would think that having about 5 families to begin would be enough to get started. Once the Promune was in operation I believe it would attract others.

What does this have to do with OpenNMS? Not much, except that people involved in the project seem to like thinking about stuff like this. OpenNMS itself is a little like an intentional community. Respect is built on merit, and while the community itself is large there is a much smaller group of people at its heart.

Also, OpenNMS is able to compete with products like OpenView and Tivoli, which are definitely “wealthy” products, yet it is produced on a middle class budget. Seeing how successful OpenNMS has been (and where it is going), the Promune doesn’t sound so far fetched.

Ah, thanks so much for the OpenID login! SO much easier 🙂 I’ve wanted to comment a few times, and thought “oh man, registering…yech”

Today I was inspired to say that this thought of an ideal community is awesome.

The only problem that I see with it is that people will always be people, and some are good, and some aren’t so good. Statistically, it seems like there are always some who don’t pull their weight, and some will always abuse and collect power.

The idea of living in small discrete communities where eveyone works together for the betterment of the collective is…smurfy. I’d be interested to see how it worked out in practice. Heck, if I remember correctly, even Biodome didn’t work out right.