The first post I made on this blog was on this date in 2003. Rather than engaging in my usual anniversary navel-gazing, I wanted to respond to a post I saw recently on Mastodon.

Disclaimer: I currently work for Amazon Web Services. The ideas and thoughts presented here are my own and may or may not reflect those of my employer.

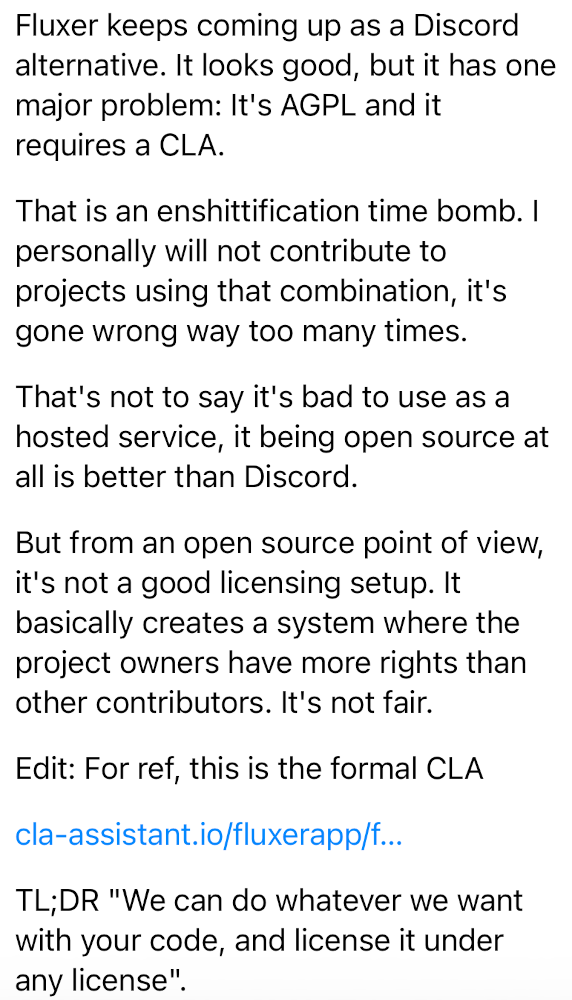

Recently the discussion platform Discord decided to implement age verification, and this has sent people looking for alternatives. I came across this post:

Now I want to stress that making the decision whether or not to contribute to an open source project is 100% personal. Every answer is valid. If you don’t like the Affero GPL (AGPL) or Contributor License Agreements (CLAs) that’s cool. You do you.

But that doesn’t mean I am not going to try to change your mind (grin).

First I want to talk about CLAs. When it comes to free and open source software I find myself in the minority when I point out that not only do I like CLAs, they can be very beneficial to a project’s success.

When I went to actually look at the CLA mentioned in the post, I couldn’t find it. I did find a Reddit thread that it looks like Fluxer has removed the CLA requirement (it still shows up in the CONTRIBUTING.md file as I type this). Let me explain why I think this is a shame.

CLAs usually have two main parts. The one that people focus on concerns copyright assignment. Frequently projects will ask to own the copyright for any contributed code.

But they serve another, much more important, role. The first thing CLAs do (usually) is ask for the contributor to attest that they have the right to contribute the code. This is more important than it seems, especially in this new world of “vibe coding”.

You may think, hey, big deal. If someone is willing to steal code, signing a CLA won’t change that. But studies have shown that simply reminding people about obligations like this can significantly reduce infractions. In researching this post I found a study from 2023 showing that having students sign a page promising to respect the university’s honor code before starting an exam reduced cheating.

Think about it. You are a small open source project. Someone submits code for a feature that becomes very popular. People become drawn to the project because of it. Then the maintainers find out that the code was actually lifted from another application and they don’t have the rights to use it.

Of course the project will need to remove it, and they may face legal consequences. They will have to choose to either remove the popular feature entirely or to try to come up with a “clean room” implementation of the offending code. I also think that by at least asking for the committer to attest that they own the could will help mitigate legal consequences. It shows a best effort by the project to insure their software is an original work.

I will admit that I don’t know of an instance of this happening (my research seems to return more cases of proprietary software applications illegally using open source code) but perhaps this is due to having people sign CLAs (grin).

Let’s get back to the other part of CLAs, copyright assignment. This is the more contentious part.

If I am remembering correctly, MySQL was one of the first major projects to require copyright assignment. And it was 100% assignment: you write some code to improve MySQL and when you contribute it you lose the copyright. This always seemed wrong to me, but, as mentioned above, you do you. If you are cool with that I am cool with that.

I am passionate about CLAs because at OpenNMS we had to face these issues. We were a tiny company with a small, but dedicated, community. When we wanted to consider a CLA we turned to the community at large, and it was suggested, by someone outside of the commercial entity, that we adopt Sun’s CLA. This CLA introduced the concept of dual copyright. It is possible to have multiple owners of a piece of intellectual property.

Think, for example, of a book with two authors. They may come together to write a novel, and then one of them could decide to write a sequel on their own. It wasn’t a unique concept within the realm of copyright with respect to printed works, but it was new in the open source world.

So why is copyright assignment important? Well, that brings me to the other part of the post: licensing.

OpenNMS was very much a corner case. When I joined the project it was as an employee of a company called Oculan. Nine months after joining Oculan they decided to cease work on OpenNMS, and I decided to take over the project. As part of the deal I got the domain names and their blessing to continue working on it, but I did not get the copyright.

A few years later, another company took the OpenNMS code and made a proprietary product out of it. This was obviously wrong and illegal, but when we tried to address it the offending company stated that if they were using OpenNMS code, it was the Oculan code and not anything we had written, therefore we had no standing. We knew this wasn’t true, but the fact that we didn’t own the majority of the code was definitely an impediment to any remediation.

This was devastating to us. Why struggle so hard to build a great application when someone with some VC money can just take it, change the front end, and profit.

My business partner and I decided to take a huge risk. We took out second mortgages on our homes to underwrite a large loan in order to buy the copyright to the code base from the company that bought Oculan’s assets after they ceased operations. We were lucky that our business was profitable and over three years the company paid off the loan, but there was no guarantee that was going to happen.

Eventually we owned the copyright and managed to get everyone who had contributed over the years to sign the CLA. Of course by this point the company that was making a proprietary version of OpenNMS had gone out of business, but it did cause us and the community to seriously examine possible future threats to our project.

We had this grand dream of being able to offer OpenNMS as a cloud service. It never happened, mainly because taking a huge, somewhat monolithic Java application and making it cloud native was a challenge, but we did see people hopping into our discussions that were obviously looking to do the same thing.

To prevent this from being done easily (see the above note about throwing VC money at commercializing an open source project) the community suggested we adopt the Affero GPL.

Prior to the license change, OpenNMS was GPLv2. Now the issue that arose when Software as a Service (SaaS) became a thing is that consumers were now just renting the output of an application versus getting a copy of the application. Most software licensing, at least at the time, was based on copyright law. No copy? Well, then copyright doesn’t apply (note the legal background on this is way more nuanced, but I’ve already lost two of my three readers by this point and I am also not a lawyer).

The AGPL was created to close this loophole.

When OpenNMS switched to the AGPL an interesting thing happened. A number of companies, many of them household names, contacted us to say they were using OpenNMS but they were not allowed to use AGPL software. Could anything be done?

Our solution? We contracted with Aaron Williamson to write a new license that was basically the GPL with an added clause that you could not make a SaaS offering of OpenNMS. Users were given a choice: use the software under the open source AGPL for no cost, or pay us to license it under the new, proprietary license.

That revenue was, in a large part, why we were able to survive, and we could not have done it without owning the copyright to the code.

Ultimately when considering to be a part of an open source community, it comes down to trust. Our small community trusted us to keep OpenNMS open, and we earned that trust. My dream was to have a SaaS version of OpenNMS with an “escape button”. Press the button and you could download all of your configurations and all of your data and easily host it yourself with zero loss of functionality. Anything that was “OpenNMS” would always be published under an open source license.

Getting back to the Mastodon post that started this whole thing, if you don’t like the AGPL, that’s fine. But realize that it is one of the few ways a company behind an open source project can build intellectual property (one other is trademarks but that is another contentious topic). If you like the project, trust the team behind it, and want it to be successful, what do you lose?

And I want to point out that having a permissive license is no guarantee that the code will be more open. In fact, there are a number of very large, very popular open source projects that are “vendor controlled”. For $REASONS I need to be a bit vague here but when a single company produces more than 50% of a project’s code, they basically control it. The ones I’m thinking about commercialize permissively licensed software by offering SaaS versions with more features that you don’t get, and probably will never get, in the open source version. They don’t need copyright assignment because the license itself allows for the creation of proprietary derivative works.

And this doesn’t begin to address companies that start out explicitly with a permissive license just to switch it once the community of users reaches a certain size, known as the license “rug pull”.

This can create its own irony. When Redis changed its license from a permissive open source one to one that limited derivative works, several maintainers decided to create a fork called Valkey. The original BSD 3 Clause license allowed them to change the license to more restrictive one, but they decided to keep the BSD license as that was the one that the community chose when they built the application. The irony is that this allows Redis to incorporate Valkey code into their product, and it is my understanding they have.

Redis has backtracked and adopted the AGPL as well. I hate that we missed an opportunity to see what would have happened had they done this in the first place. To me the AGPL is the best license for both remaining open source and concentrating some control in the hands of the entity that owns the copyright. This control, to me, is not a bad thing in most cases. As the original poster pointed out, it can be, but in my experience it really does help young, small, open source companies compete.

The person who wrote the original post was looking at Fluxer as a Discord replacement. From what I can tell it is, like a lot of open source projects, the work of one person, Hampus Kraft. Their Github repo shows two contributors. My research found a company called Fluxor Platform AB registered in Sweden, and the best guess is that they have less than four employees. Doesn’t really sound like Evil Corp. to me.

Billions of people use open source software every day, but very few people have tried to make a business around it. It is difficult, and in my experience those few that are successful do so by earning trust with their users. I just wanted to share this viewpoint to those users of open source software who don’t like things like the AGPL and CLAs. Do you trust the people who make the software you use? Do you want them to be successful and to keep making that software better? Put yourself in their shoes before dismissing them.

And as always, you do you.